Weekly Reports from Jordan

Choose Year: or Choose week

What to Expect in This Week's Report

- John McDowell of Pacific Union College and chief photographer on the project this summer writes about life and thought on the excavation, with a focus this week on popular perceptions about the dig and its purpose.

- Kent Bramlett of La Sierra University and chief archaeologist on the dig describes briefly the archaeological progress of the week in terms of small finds and exposed architecture.

- Douglas Clark of La Sierra University and director of the project includes notes about this past weekend's visit by La Sierra University president, Randal Wisbey, his wife Deanna and their son Alexander, along with nearly the entire `Umayri team, to Petra, one of the new Seven Wonders of the World. He also describes the purchase of a bedouin tent to be shipped to La Sierra for use on campus.

- In addition, Doug Clark and John McDowell report on what they have overheard or observed over the past week.

- Please check the additional weekly report entitled 2010 `Umayri Participants for individual and group photos of everyone on this season's excavation team.

All photos by John McDowell

What's It All About?

About this time in the season, when one has been digging, hauling guffas to the sift, removing rocks, and finding not much other than pottery sherds—and one has been doing this day after day in dry desert heat—the question of "why?" and "what am I doing?" can surface and be brushed off for examination.

About this time in the season, when one has been digging, hauling guffas to the sift, removing rocks, and finding not much other than pottery sherds—and one has been doing this day after day in dry desert heat—the question of "why?" and "what am I doing?" can surface and be brushed off for examination.

Textbook reasons are, of course, on hand. If one is an archaeologist, the point of excavating is clear—to recover, record, analyze, and preserve. (Unless you are Monique Vincent – PhD student in archaeology at the University of Chicago, who has worked on many digs, and is currently a field supervisor at ‘Umayri, who stated unequivocally that the point of archaeology is very clear: "Not making your supervisor mad!") For ‘Umayri this means, in particular, understanding who the people were who lived here, how they lived, and then recording and preserving what one does find. What is found is most often fragmentary—what was left behind after the move out of the house.

One can think of archaeology as season after season building a narrative about the past from scant clues left behind by the movers. Is this important? I had the privilege of being present in a meeting with the new Director General of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Dr. Ziad Al-Sa`ad. What became clear in listening to him is that ‘Umayri, a relatively small site without the grandeur of the Roman city of Jarash or of the great temple in Petra, nevertheless is significant to Jordan because of the domestic architecture—the best preserved

One can think of archaeology as season after season building a narrative about the past from scant clues left behind by the movers. Is this important? I had the privilege of being present in a meeting with the new Director General of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Dr. Ziad Al-Sa`ad. What became clear in listening to him is that ‘Umayri, a relatively small site without the grandeur of the Roman city of Jarash or of the great temple in Petra, nevertheless is significant to Jordan because of the domestic architecture—the best preserved  four-room house in the whole of the Levant—and because of what it reveals of the Bronze and Iron Ages in Jordan, eras that are not as well represented as the later Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic periods. What is revealed at ‘Umayri thus becomes an important chapter in the narrative of ancient life in Jordan.

four-room house in the whole of the Levant—and because of what it reveals of the Bronze and Iron Ages in Jordan, eras that are not as well represented as the later Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic periods. What is revealed at ‘Umayri thus becomes an important chapter in the narrative of ancient life in Jordan.

When, however, one is not an archaeologist, and one is volunteer who has paid money to come and work in the heat digging through what appears to be rubble, it is at times difficult to know what one is contributing to the larger narrative—is it barely a sentence, or even a word? A dig, by its very nature, is hierarchical in that one has a director in charge of the whole operation, a chief archeologist, field supervisors, square supervisors and then the volunteers and local workers who do most of the digging, the sifting, and the rock removal. When one is down in a trench it is possible to lose sight of the larger picture.

How that big picture is composed is personal. When asked what archaeology is, Hew Murdoch, an archaeology sophomore at La Sierra University replied: "Good question. I'm still searching for an answer. All I know is that I've been digging in the dirt since I was four."

How that big picture is composed is personal. When asked what archaeology is, Hew Murdoch, an archaeology sophomore at La Sierra University replied: "Good question. I'm still searching for an answer. All I know is that I've been digging in the dirt since I was four."

Sashiere Stewart, a student at Mt. Royal University in Calgary said, "It's really cool—finding stuff, and then hypothesizing, putting it into context and then discovering that sometimes you're right and sometimes you're wrong."

Sashiere Stewart, a student at Mt. Royal University in Calgary said, "It's really cool—finding stuff, and then hypothesizing, putting it into context and then discovering that sometimes you're right and sometimes you're wrong."

For Jillian Logee, also from Mt Royal, archaeology is "like a Christmas present from someone who does not know you very well—sometimes they are spot on, and you get what you want, and then sometimes you get a pet rock!"

For Jillian Logee, also from Mt Royal, archaeology is "like a Christmas present from someone who does not know you very well—sometimes they are spot on, and you get what you want, and then sometimes you get a pet rock!"

Canty Wang, recent La Sierra graduate who will be entering medical school this fall, explains– "We are the garbage cleaners of ancient history." She goes on to put it another way: "It's like working at McDonald's—you ride the bus to work every day, you work long hours, and  your treasure is in the Happy Meal!" She continues by saying that it is "more rewarding than McDonald's in the sense that the pieces one finds connects people of today with people of the past. This process of connection broadens our human understanding. Today most of us are focused on the present and the future—our jobs and what we will do or accomplish. It becomes important then to understand ourselves backwards through time."

your treasure is in the Happy Meal!" She continues by saying that it is "more rewarding than McDonald's in the sense that the pieces one finds connects people of today with people of the past. This process of connection broadens our human understanding. Today most of us are focused on the present and the future—our jobs and what we will do or accomplish. It becomes important then to understand ourselves backwards through time."

For Ruth Kent, a veteran for whom this is her 5th season at ‘Umaryi (when she is not on the dig she is a pastor whose parish is a senior living center in Washington D.C.), she explains that her motives for coming her first season had nothing to do with archaeology. She came willing to dig during the week as the price for being able to go on the weekend tours—Amman, Petra, Jarash, Umm Qays, the Dead Sea and all the other places one visits. She found, however, that she "very unexpectedly fell in love with archaeology." To her surprise, she fell in love with digging in dirt, fell in love with Jordan. She dreams about it between seasons. Her family and friends know that every other summer she is on the dig. The point of it? "I love it. I enjoy everything about it. I love the people." If she is in a small way contributing to human knowledge, that's OK. That's not her motivation. She goes on to say, "It's a different kind of community—different from all the other kinds I move through. This is an isolated community: the bonding over hardships—having humor to help get us through. It is an experience that is very difficult to explain. Only those who have been through it, truly know what it means."

For Ruth Kent, a veteran for whom this is her 5th season at ‘Umaryi (when she is not on the dig she is a pastor whose parish is a senior living center in Washington D.C.), she explains that her motives for coming her first season had nothing to do with archaeology. She came willing to dig during the week as the price for being able to go on the weekend tours—Amman, Petra, Jarash, Umm Qays, the Dead Sea and all the other places one visits. She found, however, that she "very unexpectedly fell in love with archaeology." To her surprise, she fell in love with digging in dirt, fell in love with Jordan. She dreams about it between seasons. Her family and friends know that every other summer she is on the dig. The point of it? "I love it. I enjoy everything about it. I love the people." If she is in a small way contributing to human knowledge, that's OK. That's not her motivation. She goes on to say, "It's a different kind of community—different from all the other kinds I move through. This is an isolated community: the bonding over hardships—having humor to help get us through. It is an experience that is very difficult to explain. Only those who have been through it, truly know what it means."

It is an experience like no other— rising at 4:15 am, the living conditions, the constant digging, the short showers, the routine day after day—it's exhausting. For some it is tedium that they have difficulty coping with. Some fall in love. A big part of the experience—is finding things. It is exciting to find, after a lot of hard work, a door to a small shrine, a seal, or even the Mother of all Grinding Stones.

It is an experience like no other— rising at 4:15 am, the living conditions, the constant digging, the short showers, the routine day after day—it's exhausting. For some it is tedium that they have difficulty coping with. Some fall in love. A big part of the experience—is finding things. It is exciting to find, after a lot of hard work, a door to a small shrine, a seal, or even the Mother of all Grinding Stones.

However, more often than not, one finds things out about one's self—how one is able to cope, get along with others, adapt to the conditions. One is never the same after the dig. The things one finds about one's self are in some sense more valuable than anything.

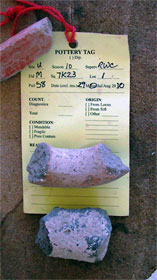

Archaeological Finds from Week Four

This week we have been pleased with the progress made while also keeping an eye on the limitations of our time left in Jordan. We know that the remaining days will pass quickly, but many of our objectives this season are in reach and beginning to be achieved.

The team working in Field A has uncovered more of the floor of their late 13th-century BC house. This proved more difficult than expected. The floor near the hearth was easy to identify because of the ash and flat-lying broken pottery there. But tracing it in the eastern part of the house was challenging. The fallen mudbrick in that part of the house hadn't burned very much at the time of the destruction of the building and it reconsolidated into a hard mass that was almost as compact as an earth floor. However, after sometimes tedious excavation peels, the work of Nicole and Vera, and Sashiere and Audrey has paid off. What they found were two surfaces, not one.

The team working in Field A has uncovered more of the floor of their late 13th-century BC house. This proved more difficult than expected. The floor near the hearth was easy to identify because of the ash and flat-lying broken pottery there. But tracing it in the eastern part of the house was challenging. The fallen mudbrick in that part of the house hadn't burned very much at the time of the destruction of the building and it reconsolidated into a hard mass that was almost as compact as an earth floor. However, after sometimes tedious excavation peels, the work of Nicole and Vera, and Sashiere and Audrey has paid off. What they found were two surfaces, not one.

Now that we know the house had two phases, we better understand other things about it that had puzzled us. A small curtain wall behind the hearth appeared to have a layer of earth beneath it and above the level of the hearth. That didn't make a lot of sense unless we postulated two phases. Now we understand that this layer of mixed clay and chalky plaster is what the inhabitants used to level and resurface their floor at some point during a renovation. Next door, Ken, Michaela and Aran, are still digging to find the floor of the neighboring house. In the room they are excavating, the destruction fire burned the mud-brick to deep reds and oranges. This week as they were digging through the brick they came down on a huge basalt lower grinding stone or saddle quern. It is the largest lower grinding stone that we have found at ‘Umayri, an truly impressive (right Ken?). Each house probably had its own, and a significant portion of each day would have seen the womenfolk of the ancient household sitting before it grinding wheat and barley into flour for daily bread.

Now that we know the house had two phases, we better understand other things about it that had puzzled us. A small curtain wall behind the hearth appeared to have a layer of earth beneath it and above the level of the hearth. That didn't make a lot of sense unless we postulated two phases. Now we understand that this layer of mixed clay and chalky plaster is what the inhabitants used to level and resurface their floor at some point during a renovation. Next door, Ken, Michaela and Aran, are still digging to find the floor of the neighboring house. In the room they are excavating, the destruction fire burned the mud-brick to deep reds and oranges. This week as they were digging through the brick they came down on a huge basalt lower grinding stone or saddle quern. It is the largest lower grinding stone that we have found at ‘Umayri, an truly impressive (right Ken?). Each house probably had its own, and a significant portion of each day would have seen the womenfolk of the ancient household sitting before it grinding wheat and barley into flour for daily bread.

In Field H, the interior divisions of the similarly dated building are becoming clearer, even as the search for the surfaces has slowed the pace of clearance. Some of the interior walls are constructed with a "quoin and pier" technique, which is an archaeological term for walls formed by filling the spaces between pillar-like piers with (it appears) hastily-stacked stones.

In Field H, the interior divisions of the similarly dated building are becoming clearer, even as the search for the surfaces has slowed the pace of clearance. Some of the interior walls are constructed with a "quoin and pier" technique, which is an archaeological term for walls formed by filling the spaces between pillar-like piers with (it appears) hastily-stacked stones.  We have seen this construction technique most commonly in the late Iron Age but now we have something like it quite a bit earlier. As Monique and Kambiz (Kambiz Fathi, who recently arrived as a second-half-season team member) were clearing some stones near the doorway leading from the cobbled room to a central room, Kambiz removed a rock and Monique reached down to pick up what appeared to be a piece of pottery. Reports have it that there was something like a squeal heard! The piece of pottery was actually a miniature door of some kind. Monique thinks it may be a door for a model shrine. It was shaped from a potsherd, but carefully chipped to resemble a big stone door with hinge nubs at top and bottom.

We have seen this construction technique most commonly in the late Iron Age but now we have something like it quite a bit earlier. As Monique and Kambiz (Kambiz Fathi, who recently arrived as a second-half-season team member) were clearing some stones near the doorway leading from the cobbled room to a central room, Kambiz removed a rock and Monique reached down to pick up what appeared to be a piece of pottery. Reports have it that there was something like a squeal heard! The piece of pottery was actually a miniature door of some kind. Monique thinks it may be a door for a model shrine. It was shaped from a potsherd, but carefully chipped to resemble a big stone door with hinge nubs at top and bottom.

Field L has been progressing on two fronts. In the two newly opened squares, the archaeologists, including a new arrival and wife of Kambiz, Evanthia Hatziminaoglou, are beginning to identify wall lines that connect with structures to the east. In the area of the Hellenistic farmstead, David, Mary, and Amanda (David's wife who also joined for the second half) have been puzzling over a possible oil press installation. The installation was actually covered over by the later Hellenistic construction and thus dates to an earlier period in the late Iron Age (6th – 5th centuries BC). The beam weights (the stones with holes bored through) were found during a previous season and David has been puzzling ever since about where the rest of the olive oil press was located. This week as he and team were excavating a remaining balk, a peculiar round stone and plastered area were found in proximity to the weights. While some questions remain, we think this might be part of the long-sought-after oil press.

Field L has been progressing on two fronts. In the two newly opened squares, the archaeologists, including a new arrival and wife of Kambiz, Evanthia Hatziminaoglou, are beginning to identify wall lines that connect with structures to the east. In the area of the Hellenistic farmstead, David, Mary, and Amanda (David's wife who also joined for the second half) have been puzzling over a possible oil press installation. The installation was actually covered over by the later Hellenistic construction and thus dates to an earlier period in the late Iron Age (6th – 5th centuries BC). The beam weights (the stones with holes bored through) were found during a previous season and David has been puzzling ever since about where the rest of the olive oil press was located. This week as he and team were excavating a remaining balk, a peculiar round stone and plastered area were found in proximity to the weights. While some questions remain, we think this might be part of the long-sought-after oil press.

This week has been all about surfaces, and Field M was no exception. With the removal of the balks last week, the field really opened up. We understand better two phases of cobble surfaces which are connected architecturally with a late Iron Age building. The earlier cobble surface was better preserved so Lizzy's team recorded the fragments of the later level and removed it to reveal the maximum exposure of the earlier surface. Evidence of hard plaster in and around some of the stones of that surface shows that it was constructed to be very durable. Perhaps it was an open courtyard for a large house, or even a plaza. We really need to open new squares in Field M next season to find out.

As we look to next week, we know we won't get everything done. But we are optimistic that if we work hard, most of our primary questions can be answered. Stay tuned!

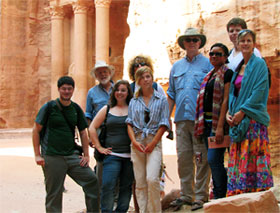

To Petra with the President

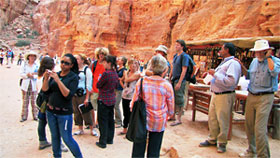

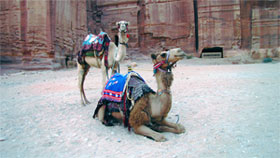

A part of each season's planned tours at Tall al-`Umayri, the major trip to Petra is always a favorite. Typically held mid-season, the trip provides motivation to keep going through the first several weeks of hard labor in the field, and grand memories to live by for the rest of the season. Timed perfectly, the visit of La Sierra University president Randal Wisbey, his wife Deanna and son Alexander coincided with our Petra trip.

Now classified as one of the "new" Seven Wonders of the World, Petra is drawing huge crowds who are willing to pay continually rising entry fees, moving up to as much as JD75 (=USD105) in the near future, some say. Because our team works in cooperation with the Department of Antiquities, entry fees are waived each year, making it easier for foreign archaeologists to learn more about Jordan's cultural heritage.

Our hotel this summer, the Petra Guest House, somewhere around 3.5-star accommodations, compared favorably to the lower rating of our camp accommodations, due in large part to air conditioning and bathrooms in every room. There is no hotel in Wadi Musa, where Petra is located, closer to the entry gate into Petra than the Guest House. Literally attached to the back wall of the gate house, our hotel is 75 steps away from the gate to the magical, rose-red-sandstone world of Petra. Victorian traveler Dean Durgon's famous lines come to mind:

Our hotel this summer, the Petra Guest House, somewhere around 3.5-star accommodations, compared favorably to the lower rating of our camp accommodations, due in large part to air conditioning and bathrooms in every room. There is no hotel in Wadi Musa, where Petra is located, closer to the entry gate into Petra than the Guest House. Literally attached to the back wall of the gate house, our hotel is 75 steps away from the gate to the magical, rose-red-sandstone world of Petra. Victorian traveler Dean Durgon's famous lines come to mind:

Match me such a marvel,

sure in eastern clime,

a rose-red city,

half as old as time.

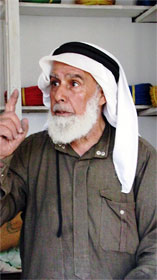

Our descent from the entry gate to the opening of the Siq (1-km-long erosion canyon) allows for introductory conversations about the history of Petra. Occupied from neolithic times, the area was later home to Edomites in the 8th-7th centuries BC. But the major inhabitants whose remains greet visitors to this day were the Nabateans, Arab tribes which dominated an extensive network of trade routes from the 4th century BC through the beginning of the 2nd century AD, giving way in AD 106 to the Romans. Christians built churches in Petra in the 6th century AD, the major one of which produced 152 burned leather scrolls now being conserved and published by international groups of scholars at the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman. From Crusader times until the early 19th century, Petra was lost to the western world, "rediscovered" by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss explorer, on 22 August 1812. Over the past hundred or so years, the Bdoul bedouin have lived in Petra, but most have now been resettled in a new village just outside Petra, Umm Sayhoun.

Our descent from the entry gate to the opening of the Siq (1-km-long erosion canyon) allows for introductory conversations about the history of Petra. Occupied from neolithic times, the area was later home to Edomites in the 8th-7th centuries BC. But the major inhabitants whose remains greet visitors to this day were the Nabateans, Arab tribes which dominated an extensive network of trade routes from the 4th century BC through the beginning of the 2nd century AD, giving way in AD 106 to the Romans. Christians built churches in Petra in the 6th century AD, the major one of which produced 152 burned leather scrolls now being conserved and published by international groups of scholars at the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman. From Crusader times until the early 19th century, Petra was lost to the western world, "rediscovered" by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss explorer, on 22 August 1812. Over the past hundred or so years, the Bdoul bedouin have lived in Petra, but most have now been resettled in a new village just outside Petra, Umm Sayhoun.

The greater draw of Petra is the Siq itself and the monuments to which it leads. And primary among the carved monuments is Al Khazneh, the Treasury, the first "tomb" greeting those exiting the Siq. While of tremendous interest to students of the archaeology of ancient Petra, the Treasury carries intrigue for Indiologists wanting to know if the Indiana Jones movie really had it right in its depiction of this temple at the end of the Valley of the Crescent Moon where the Holy Grail could be found. It didn't–no secret passageways, no deadly, low-flying circular saw blades, no booby-trapped pavement, no canyon, no aging knights in tarnished armor, no choosing wisely or unwisely.

The greater draw of Petra is the Siq itself and the monuments to which it leads. And primary among the carved monuments is Al Khazneh, the Treasury, the first "tomb" greeting those exiting the Siq. While of tremendous interest to students of the archaeology of ancient Petra, the Treasury carries intrigue for Indiologists wanting to know if the Indiana Jones movie really had it right in its depiction of this temple at the end of the Valley of the Crescent Moon where the Holy Grail could be found. It didn't–no secret passageways, no deadly, low-flying circular saw blades, no booby-trapped pavement, no canyon, no aging knights in tarnished armor, no choosing wisely or unwisely.  Only a carved-out cube, forty feet on a side, with a couple of small niches in the sidewalls. Following negotiations with government offices and officials, and after waiting for a lull in the number of tour groups photographing the Treasury, we were able to gain five minutes inside the main room in the structure, otherwise closed off to visitors.

Only a carved-out cube, forty feet on a side, with a couple of small niches in the sidewalls. Following negotiations with government offices and officials, and after waiting for a lull in the number of tour groups photographing the Treasury, we were able to gain five minutes inside the main room in the structure, otherwise closed off to visitors.

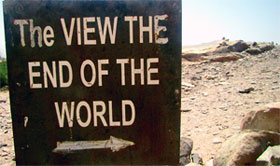

Other important must-see locations in Petra include the High Place, Ad-Dayr (the Monastery), churches, tombs, incredible vistas.

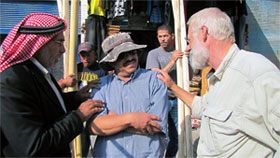

Bedouin Tent Bound for La Sierra

The La Sierra University campus will soon see a new addition to its expansive lawns, palm-lined sidewalks and arboretum ambiance–a genuine black goat-hair bedouin tent, a Bayt Shair. Made in Madaba, Jordan, a few kilometers from the `Umayri excavations, the tent will be shipped home with the objects and artifacts we have excavated over the course of the summer. It will be used for special occasions tied to archaeology, like La Sierra's annual Archaeology Discovery Weekend in mid-November each year. We have also purchased accessories such as original, traditional coffee pots, carpets and wall hangings. Anyone wishing to donate toward the acquisition of other bedouin tent furniture, email me.

Observed

Overheard

Carrie Duncan: "Oh, stratigraphy! How you rule our lives!"

Nikki Oakden in response: "Maybe we should pay tithe to it!"

Vera Kopecky, in response to an email from her daughter, Henrietta (an `Umayri veteran and La Sierra University alumna) asking for news from the dig: "I'm no snitch. What happens at `Umayri stays at `Umayri."

Doug Clark: "In your square, Vera, what happens in the balk, stays in the balk!"

Nikki Oakden, supervisor of a new square this season that has produced nothing but rock tumble so far: "Tumble is the Days of Our Lives . . . like sand through the sifter."

Graeme Waring-Crane: "There is no more irritating sound than the wake-up bells at 4:15 am. I now crank up loud music to go off at 4:10 just so that I am not wakened by those bells."

Abu Issa, foreman of local laborers at `Umayri: "Ouch!" (at least) as maybe one hundred stones from a support wall fell on him in a weekend repair operation. Fortunately, no major injuries, but many painful abrasions. Doug Clark took him to a nearby clinic where they entered the plain-looking building, turned right to a waiting area filled with mothers and their small children, left to a reception desk, left to a physician's office, right to a nursing station, back again to the physician's office, right to the pharmacy, left again to the reception office, right once more to the pharmacy, then out the door and back to work. It took 20 minutes for the visit, all covered by Abu Issa's medical card, but it will take several days for the pain to go away. He's a tough guy.

In Field L there has been discussion of new food combinations. A recipe Olivia swears by: To a ladle of Cream of Wheat, add a mashed hard-boiled egg, Zahtar—a common spice mix—to taste, and heap a tablespoon of Lebna (yoghurt). Mix well.