Weekly Reports from Jordan

Choose Year: or Choose week

Dig Dirt

John McDowell

We did dirt. We haul dirt to sifts. We sweep dirt. We move rocks. We measure and draw rocks. With hand picks and trowels we peel away layers of time. We are narrative seekers.

We did dirt. We haul dirt to sifts. We sweep dirt. We move rocks. We measure and draw rocks. With hand picks and trowels we peel away layers of time. We are narrative seekers.

Early morning is the best time on the tell—the air, night cooled still welcomes. We arrive before sunup and the first, most pressing task is to photograph each dig field before the sun arrives to cast shadows. I rush to set up camera and tripod, while square supervisors sweep the dirt. The purpose here is to document—and archaeology works only because of careful and consistent documentation—each day’s progress.

Early morning is the best time on the tell—the air, night cooled still welcomes. We arrive before sunup and the first, most pressing task is to photograph each dig field before the sun arrives to cast shadows. I rush to set up camera and tripod, while square supervisors sweep the dirt. The purpose here is to document—and archaeology works only because of careful and consistent documentation—each day’s progress.  The photos are numbered and placed in a database so what happens is remembered as each layer of earth is peeled away. The recovery of architecture and objects requires the removal of earth—a 5 cm layer at a time Archeology is also the careful science of destruction.

The photos are numbered and placed in a database so what happens is remembered as each layer of earth is peeled away. The recovery of architecture and objects requires the removal of earth—a 5 cm layer at a time Archeology is also the careful science of destruction.

Once photos are done, a variety of activities begin. Depending at what stage each square is at—some commence digging and sifting right away --- others take elevation levels; some might draw top plans of significant features.

Once photos are done, a variety of activities begin. Depending at what stage each square is at—some commence digging and sifting right away --- others take elevation levels; some might draw top plans of significant features.

The right way to dig is with a steady rhythm of pick and then trowel. The dirt is scooped into a guffa. The guffa is then dumped into a sift, a counter is clicked, and then the dirt is sifted; we look for pottery sherds, bone, flint and anything that might be made by humans: a seal for example. In actual practice, to get the digging done, there are those who will go to all sorts of lengths. To support the recovery of objects and architecture, a lot of associated data is needed for analysis and understanding to be successful. This includes measurements of various types: soil color analysis, GPS data, elevations, and placement measurements. Archaeology is about paying attention to such details.

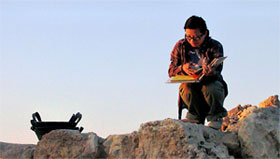

The right way to dig is with a steady rhythm of pick and then trowel. The dirt is scooped into a guffa. The guffa is then dumped into a sift, a counter is clicked, and then the dirt is sifted; we look for pottery sherds, bone, flint and anything that might be made by humans: a seal for example. In actual practice, to get the digging done, there are those who will go to all sorts of lengths. To support the recovery of objects and architecture, a lot of associated data is needed for analysis and understanding to be successful. This includes measurements of various types: soil color analysis, GPS data, elevations, and placement measurements. Archaeology is about paying attention to such details.  This involves drawing top plans of the square – drawing every rock and feature before peeling away another layer. This year, inputting data electronically is being tested by Monique with the use of an iPad. Here she is working with her iPad—while Doug Clark is trying to figure out what an iPad is!. All the data, along with photographs, eventually go into a large database. The field supervisors command their squares with firmness and clear direction. Sometimes they have to inspire their troops anyway they can.

This involves drawing top plans of the square – drawing every rock and feature before peeling away another layer. This year, inputting data electronically is being tested by Monique with the use of an iPad. Here she is working with her iPad—while Doug Clark is trying to figure out what an iPad is!. All the data, along with photographs, eventually go into a large database. The field supervisors command their squares with firmness and clear direction. Sometimes they have to inspire their troops anyway they can.

A second breakfast of falafel and schwarma sandwiches arrives at 9:30.

A second breakfast of falafel and schwarma sandwiches arrives at 9:30.  All gather in the tent and eagerly eat. Kent then performs the ritual slaughter of the watermelon and by tradition we stand on the edge of the tell spitting seeds and seeing who can throw their rind the farthest. Some rest and try to sleep. All too soon Doug hurries us back to the trenches where we occasionally we find critters such as this spider. Soon dirt and rocks are again being removed. Works ends around 12:30. Final notes are taken. Tools, equipment, and water bottles are gathered up.

All gather in the tent and eagerly eat. Kent then performs the ritual slaughter of the watermelon and by tradition we stand on the edge of the tell spitting seeds and seeing who can throw their rind the farthest. Some rest and try to sleep. All too soon Doug hurries us back to the trenches where we occasionally we find critters such as this spider. Soon dirt and rocks are again being removed. Works ends around 12:30. Final notes are taken. Tools, equipment, and water bottles are gathered up.  Tired and covered with the finest of dig dirt patina, we head to the buses and back to camp for a quick, yet wonderful and blessed shower before lunch at 1:00 where finds of the day are announced.

Tired and covered with the finest of dig dirt patina, we head to the buses and back to camp for a quick, yet wonderful and blessed shower before lunch at 1:00 where finds of the day are announced.

During the morning, usually well before second breakfast, Doug, Kent, and Ramel (the representative from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan) make the rounds to talk to the field supervisors about what is emerging, what has been found, where to continue digging. There is often discussion about surfaces and walls.

During the morning, usually well before second breakfast, Doug, Kent, and Ramel (the representative from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan) make the rounds to talk to the field supervisors about what is emerging, what has been found, where to continue digging. There is often discussion about surfaces and walls.  The details form the bedrock of the narrative we are chasing. Sometimes the ancients left few and of frustrating clues. Archaeology is the writing of a mystery novel or, as Doug Clark says, it’s a game of Clue on steroids. While the metaphors are illuminating, what we are really trying to do is piece together the gripping narrative of our human past. Archaeologists are not Indiana Jones treasure seekers. They simply want to know the answers to questions such as: Who lived here and when? How did they live? How did they build, cook, worship, and how did they die? It is a really thrilling to find a seal impression with a finger print of some person alive here thousands of years ago, or to find a hearth inside a home—the ashes still there of a distant fire where someone, a mother say, bent over a fire to make food for her family. In archaeology we seek again and again such moments. That which is lost is found and made real again. It’s why we dig dirt.

The details form the bedrock of the narrative we are chasing. Sometimes the ancients left few and of frustrating clues. Archaeology is the writing of a mystery novel or, as Doug Clark says, it’s a game of Clue on steroids. While the metaphors are illuminating, what we are really trying to do is piece together the gripping narrative of our human past. Archaeologists are not Indiana Jones treasure seekers. They simply want to know the answers to questions such as: Who lived here and when? How did they live? How did they build, cook, worship, and how did they die? It is a really thrilling to find a seal impression with a finger print of some person alive here thousands of years ago, or to find a hearth inside a home—the ashes still there of a distant fire where someone, a mother say, bent over a fire to make food for her family. In archaeology we seek again and again such moments. That which is lost is found and made real again. It’s why we dig dirt.

Overheard

“She’s the coolest field supervisor because she has water breaks!”

Olivia: “I don’t feel very feminine. hauling guffas, wielding a pick ax—[archaeology] is very masculine.” (It should be noted that all the Field Supervisors this year are women.)

Doug Clark: “The answers lie in the balk.”

Kent Bramlett our chief archeologist using sophisticated archaeological terminology when asked about a particular wall: “Oh, that’s a higgledy, piggledy wall.”

Archaeological Report

This week has been a whirlwind of progress punctuated with interesting discoveries. Excavation of the early Iron Age house in Field A is progressing steadily. Audrey Shaffer and Sashiere Stewart discovered a beautifully preserved hearth in the back room of the house. This surprised us because we typically expect cooking fires to be located in outer rooms or courtyards, not where the smoke would be difficult to ventilate. But this does not seem to have been a significant consideration in this example.

This week has been a whirlwind of progress punctuated with interesting discoveries. Excavation of the early Iron Age house in Field A is progressing steadily. Audrey Shaffer and Sashiere Stewart discovered a beautifully preserved hearth in the back room of the house. This surprised us because we typically expect cooking fires to be located in outer rooms or courtyards, not where the smoke would be difficult to ventilate. But this does not seem to have been a significant consideration in this example.  Then, if that weren’t enough for these two archaeologists, as they troweled away the collapsed mud-brick opposite the fire-ring, they found a stone platform, which we think may have been used for food preparation. Traces of hard plaster indicated the table was finished nicely with the plaster wrapping up against the wall. Elsewhere in the house, Field A team members are still digging to reach the floor which they expect to expose next week.

Then, if that weren’t enough for these two archaeologists, as they troweled away the collapsed mud-brick opposite the fire-ring, they found a stone platform, which we think may have been used for food preparation. Traces of hard plaster indicated the table was finished nicely with the plaster wrapping up against the wall. Elsewhere in the house, Field A team members are still digging to reach the floor which they expect to expose next week.

Field H: Monique’s “great wall” is gone. The removal of the lower course went rapidly as the workers could sense the end in reach. Adel, one of the Jordanians with a particularly sharp eye for detail, was clearing away the earth debris that had accumulated between wall stones when he spotted a small “lotus flower vase pendant.” This minute vase-shaped bead, made of carnelian, is a well known Egyptian-manufactured object.

Field H: Monique’s “great wall” is gone. The removal of the lower course went rapidly as the workers could sense the end in reach. Adel, one of the Jordanians with a particularly sharp eye for detail, was clearing away the earth debris that had accumulated between wall stones when he spotted a small “lotus flower vase pendant.” This minute vase-shaped bead, made of carnelian, is a well known Egyptian-manufactured object.

Work continues in the rest of Field H to figure out what kind of structure is represented by the walls being excavated from the mushed mud-brick and rubble that filled in the building when it collapsed in the 12th century BC. Shallow higgledy-piggledy walls (a technical architectural term, for those unacquainted with it!) seem to divide up the interior space of a large building characterized by otherwise sturdy walls which appear to have been built earlier. This makes us wonder if perhaps the 12th-century inhabitants remodeled an older building to suit their subsistence life way. While digging through the debris in one area of the building, Canty Wang found a seal made of light volcanic tuff. But Canty’s seal was broken in antiquity (as indicated by the weathered break) and only a little more than half remained.

Kent Bramlett mentioned to her the story of the finding of the Gilgamesh epic in the ruins of Nineveh, and how at the British Museum, translator George Smith was dismayed to find a key tablet in the series missing. Effort was made to go back to Nineveh and look for the missing tablet, like a needle in a haystack. Amazingly, they found it and were able to complete the translation. Kent joked that Canty should now look for and find the other half as Smith did for his missing tablet. He left and she looked. And to all our amazement, she found it!

Kent Bramlett mentioned to her the story of the finding of the Gilgamesh epic in the ruins of Nineveh, and how at the British Museum, translator George Smith was dismayed to find a key tablet in the series missing. Effort was made to go back to Nineveh and look for the missing tablet, like a needle in a haystack. Amazingly, they found it and were able to complete the translation. Kent joked that Canty should now look for and find the other half as Smith did for his missing tablet. He left and she looked. And to all our amazement, she found it!

Field L continues to dig through topsoil in the newly opened squares. Following the find last week of the griffin seal impression, L members seem to have honed a knack for finding seals. This week Justin Waring-Crane found a nice glyptic seal which features an ibex and a young one nursing at its belly. Justin, who is here for only a half season, and will be heading home next week, was lucky to make such a nice find. At lunchtime show and tell that day, Justin’s mother, Rebecca, was overheard quipping that her daughter made the find “just-in time.”

Field L continues to dig through topsoil in the newly opened squares. Following the find last week of the griffin seal impression, L members seem to have honed a knack for finding seals. This week Justin Waring-Crane found a nice glyptic seal which features an ibex and a young one nursing at its belly. Justin, who is here for only a half season, and will be heading home next week, was lucky to make such a nice find. At lunchtime show and tell that day, Justin’s mother, Rebecca, was overheard quipping that her daughter made the find “just-in time.”

Field M achieved its goal of removing balks this week. This process has transformed the view across the field. Now we see cobble surfaces connecting disparate walls, helping us to understand at last the sequence of their construction. Field M will be excited to begin digging deeper again, now that all the balks are gone.

Archaeological Conference

Douglas Clark

Sunday, the fourth of July, saw 130 archaeology project team members assembled in the school auditorium of the Latin Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist for a first-ever regional archaeology mini-conference. The idea for the conference came from two visits I made to annual day-long conferences among all the archaeological projects working in Cyprus.

Sunday, the fourth of July, saw 130 archaeology project team members assembled in the school auditorium of the Latin Church of the Beheading of John the Baptist for a first-ever regional archaeology mini-conference. The idea for the conference came from two visits I made to annual day-long conferences among all the archaeological projects working in Cyprus.  Each project director had 15 minutes to present the latest update on her or his project, a process that took all day. It was rather like drinking water from a fire hydrant, but brought all dig participants in the country up to date.

Each project director had 15 minutes to present the latest update on her or his project, a process that took all day. It was rather like drinking water from a fire hydrant, but brought all dig participants in the country up to date.

In Jordan, with several regional clusters of projects whose artifacts go to regional museums for study and display, the Madaba region in central Jordan is one of the most active. Directors of all the projects currently in the field in the region gave PowerPoint presentations to the assembled archaeologists, specialists, staff, and students.

In Jordan, with several regional clusters of projects whose artifacts go to regional museums for study and display, the Madaba region in central Jordan is one of the most active. Directors of all the projects currently in the field in the region gave PowerPoint presentations to the assembled archaeologists, specialists, staff, and students.

By all counts, this first annual regional mini-conference was a smashing success. It provided Father Yacoub, priest of the church and patriarch of the Madaba District, an opportunity to encourage archaeologists to share their work. It also gave students the chance to hear from archaeologists whose books they are reading in school. And in the end, the conference allowed us all to become aware of what archaeologists were doing throughout the area of central Jordan, reminding us that we are all part of a larger endeavor almost like people in antiquity who shared survival strategies with their neighbors.

By all counts, this first annual regional mini-conference was a smashing success. It provided Father Yacoub, priest of the church and patriarch of the Madaba District, an opportunity to encourage archaeologists to share their work. It also gave students the chance to hear from archaeologists whose books they are reading in school. And in the end, the conference allowed us all to become aware of what archaeologists were doing throughout the area of central Jordan, reminding us that we are all part of a larger endeavor almost like people in antiquity who shared survival strategies with their neighbors.

The program:

First Annual

Regional Archaeology Mini-conference – Madaba

Latin Church of Madaba

11:00 am-1:30 pm

4 July 2010

Welcome Speeches

Douglas Clark, Director, Madaba Plains Project-`Umayri

Father Yacoub, Patriarch, Latin Church of Madaba

Ali Al-Khayyat, Director, Madaba District of the Department of Antiquities

Barbara Porter, Director, American Center of Oriental Research

Presentations

Tall Madaba Archaeological Project

Director Debra Foran, University of Toronto

Madaba Plains Project-`Umayri

Director Douglas R. Clark, La Sierra University

Chief Archaeologist Kent V. Bramlett, La Sierra University

DoA Representative Romel Gharib, Amman District Director, DoA

Dhiban

Directors Bruce Rutledge, University of Liverpool

Benjamin Porter, UC Berkeley

Danielle Fatkin, Knox College

Wadi Thamad

Director/Chief Archaeologist Michele Daviau, Wilfrid Laurier University

Associate Director Robert Chadwick

Field Supervisors Christopher Gohm, University of Toronto

Annlee Dolan, Delta College

Survey Director Jonathan Ferguson, University of Toronto

DoA Representative Ali Al-Khayyat, Basem Mohamid

Mt. Nebo

Director Margaret Judd, University of Pittsburgh

Ataruz

Director Chang Ho Ji, La Sierra University

MEGA-Jordan

Coordinator Catreena Hamarneh, Department of Antiquities

Thanks to:

Father Yacoub for use of the Latin Church school auditorium

The Latin Church staff for logistical support

Debra Foran and her team for securing the meeting venue and for making arrangements for refreshments

La Sierra University Presidential Visit to `Umayri

La Sierra University president, Randal Wisbey, his wife Deanna, and their son Alexander, visited the `Umayri excavations this past week. They arrived in Amman Tuesday evening, 6 July, spent time with me visiting government and institutional offices on Wednesday, came out to `Umayri on Thursday, traveled to local sites of interest on Friday and are going with the group to Petra for the weekend-long, mid-season trip to one of the seven wonders of the ancient world Friday through Sunday (watch for this report next week). From there they fly to Israel, revisiting Jerusalem, the location of a year he spent teaching English in East Jerusalem and Ramallah while in college.

Our visit to the Department of Antiquities (DoA) of Jordan was important for several reasons. Dr. Ziad Al-Sa`ad is the new Director General of the DoA, having been in the office for a full three days when we met with him. An academic archaeologist and administrator at Yarmouk University in Irbid in north Jordan, he brings excellent administrative and interpersonal skills with him. He was a pleasure to talk to and was especially glad to meet the president of La Sierra University, well known around Jordan for its support of archaeology in the country.

Our visit to the Department of Antiquities (DoA) of Jordan was important for several reasons. Dr. Ziad Al-Sa`ad is the new Director General of the DoA, having been in the office for a full three days when we met with him. An academic archaeologist and administrator at Yarmouk University in Irbid in north Jordan, he brings excellent administrative and interpersonal skills with him. He was a pleasure to talk to and was especially glad to meet the president of La Sierra University, well known around Jordan for its support of archaeology in the country.  I invited him to come to Atlanta for the American Schools of Oriental Research conference in November and, on the way, to visit La Sierra during our annual Archaeology Discovery Weekend in the middle of November. He seemed quite open to the idea, if he can fit it into his schedule.

I invited him to come to Atlanta for the American Schools of Oriental Research conference in November and, on the way, to visit La Sierra during our annual Archaeology Discovery Weekend in the middle of November. He seemed quite open to the idea, if he can fit it into his schedule.

We also met with the new principal of the Amman Training College where we stay while in Jordan. Dr. Ahmad Subhi Ayyadi is gracious, forward-looking, and creative in engaging companies (especially banks) in the development of the school.  He and his staff, especially Dr. Orouba Subhi Al-Musa, Deputy Principal, and Husam Shahroor, administrator of the school and MBA graduate of La Sierra, continue to help us whenever we need it.

He and his staff, especially Dr. Orouba Subhi Al-Musa, Deputy Principal, and Husam Shahroor, administrator of the school and MBA graduate of La Sierra, continue to help us whenever we need it.

Thursday brought the Wisbeys to the site of Tall al-`Umayri where excavations, under the primary sponsorship of La Sierra University, have been running since 1984, directed by former La Sierra president, Larry Geraty. Meeting up with La Sierra faculty and students was a priority for the president and his family.

On Friday they visited Jerash, likely the second best well known archaeological site in Jordan, a major city from Roman times with remains from several archaeological periods. Upon returning to Amman, they rejoined the `Umayri team for the trip to Petra (watch for the Petra report next week).

All photos courtesy of John McDowell and Jillian Logee