Weekly Reports from Jordan

Choose Year: or Choose week

Week 4 – Archaeology Report 2

By Kent Bramlett and Photos by Jillian Logee

The second half of the season has seen a number of answers emerge to our research questions (see Weekly Report 2). This is satisfying and is part of the excitement of doing archaeology. Sometimes the answers are surprises, and usually they contain unexpected elements.

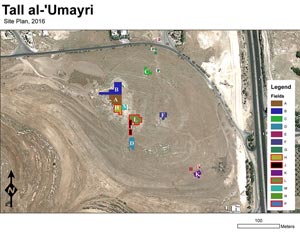

Field H. Confirmed! The wall in question was the Iron Age perimeter wall as we thought it might be. The Field H team excavated through an Iron IA (late 12th–early 11th century BC) cobbled surface and began working down through the layers. Before long, they reached a marked transition to crumbly burned mud-brick in varying hews of reds, browns, and yellows. This was familiar to several of us who excavated in other fields along the western edge of the tell. The walled town from about 1200 BC (transitional Late Bronze/Early Iron I) had met a fiery end, burning so hotly that pottery appeared to melt and limestone turned to lime powder. The roof beams and supporting posts burned and collapsed and the heat of the conflagration fired the sun-dried mudbrick which then crashed down, encapsulating everything in the buildings in 1.2-2.0 m of debris.

Field H. Confirmed! The wall in question was the Iron Age perimeter wall as we thought it might be. The Field H team excavated through an Iron IA (late 12th–early 11th century BC) cobbled surface and began working down through the layers. Before long, they reached a marked transition to crumbly burned mud-brick in varying hews of reds, browns, and yellows. This was familiar to several of us who excavated in other fields along the western edge of the tell. The walled town from about 1200 BC (transitional Late Bronze/Early Iron I) had met a fiery end, burning so hotly that pottery appeared to melt and limestone turned to lime powder. The roof beams and supporting posts burned and collapsed and the heat of the conflagration fired the sun-dried mudbrick which then crashed down, encapsulating everything in the buildings in 1.2-2.0 m of debris.

We had excavated several houses from this occupation horizon in Fields A and B. And probes in 2012 had produced similar destruction under an Iron IA (c. 1100 BC) house in Field H. So when the team reached this layer sealing against several courses of the perimeter wall, we were not surprised when the pottery recovered from the debris confirmed our expectation that this was from the same time period as the other houses. The wall also showed strong indications of phasing, having been rebuilt along the same line overtop the destruction layer, but overhanging the earlier wall-line by a few inches as is typical of rebuilt walls following mostly-buried earlier wall lines.

The excitement mounted as the probe got deeper and deeper. We really wanted to get to the floor under the destruction layer, and, ideally, dig below the floor to better understand the construction date. However, we had a problem. As the excavation probe got deeper, it became apparent that we had a safety issue. The area under excavation was bounded by two thick stone walls, one on the north, and the perimeter wall on the south. The northern wall was bulging dangerously. We decided to reinforce the excavation probe much like old mineshafts were shored with scaffolding. Our workmen from Bunayat village who work with us each season brought boards and together we created “the apparatus” as square supervisor Craig Tyson called it.

The excitement mounted as the probe got deeper and deeper. We really wanted to get to the floor under the destruction layer, and, ideally, dig below the floor to better understand the construction date. However, we had a problem. As the excavation probe got deeper, it became apparent that we had a safety issue. The area under excavation was bounded by two thick stone walls, one on the north, and the perimeter wall on the south. The northern wall was bulging dangerously. We decided to reinforce the excavation probe much like old mineshafts were shored with scaffolding. Our workmen from Bunayat village who work with us each season brought boards and together we created “the apparatus” as square supervisor Craig Tyson called it.

Following the installation of these safety measures, the excavators would descend by a ladder which was then pulled back up to provide more digging space at the bottom, and a rope and pulley system allowed the baskets of excavated material to be hoisted up and sifted for artifacts. As excavation progressed, several artifacts were recovered. A unique faience bead and stamped-impressed pottery handles were found. A basalt tripod quern and grinder complemented the discoveries (PHOTO). After excavating just over a meter down into the destruction debris, the excavators reached the floor—a very nice flagstone surface.

Following the installation of these safety measures, the excavators would descend by a ladder which was then pulled back up to provide more digging space at the bottom, and a rope and pulley system allowed the baskets of excavated material to be hoisted up and sifted for artifacts. As excavation progressed, several artifacts were recovered. A unique faience bead and stamped-impressed pottery handles were found. A basalt tripod quern and grinder complemented the discoveries (PHOTO). After excavating just over a meter down into the destruction debris, the excavators reached the floor—a very nice flagstone surface.

One question remained. Did the city wall go deeper? Only by removing part of the flagstone floor and digging down could we find out. But as is often the case in these situations, the end of the season was upon us. In two days of final excavation the team in Field H did uncover what are possibly two courses of an earlier wall below the 1200 BC wall. It is offset even more than the phases above, and due to possible disruption, is not well laid. Only another season of work can provide us with a definitive answer to the question of a Late Bronze Age wall beneath this section of the Iron Age wall.

One question remained. Did the city wall go deeper? Only by removing part of the flagstone floor and digging down could we find out. But as is often the case in these situations, the end of the season was upon us. In two days of final excavation the team in Field H did uncover what are possibly two courses of an earlier wall below the 1200 BC wall. It is offset even more than the phases above, and due to possible disruption, is not well laid. Only another season of work can provide us with a definitive answer to the question of a Late Bronze Age wall beneath this section of the Iron Age wall.

Field L, also along the southern part of the acropolis, provided another opportunity to try to locate the southern extent of the perimeter wall. And we also hoped to learn more about the Iron I period in this area. The two teams working in L under field supervisor Owen Chestnut continued their respective quests. Shaun and Josephine and later Mary Boyd, continued below the surfaces they found in the first half of the season. They identified and excavated more layers and possible surfaces. And during the last full week, they found evidence of burning and some crushed pottery. Under and around a broken storage jar they collected samples of charred grain. These will provide ideal samples for 14C dating. Short-lived samples like seeds are much preferred to wood samples because the former grew in one single year rather than over decades or centuries, thus potentially providing a more accurate date. The style of this pottery was still Iron IA and not the transitional Late Bronze/Early Iron I found over in H. Heroic attempts to dig down to the next layer in the final days were unsuccessful but we are pleased with the increased information we have about the Iron I.

Meanwhile, excavators in the other square in Field L found a very nice bin. It was lined with stones closely fit together. Subsequent work in the western half of the square focused on getting stratigraphic depth to better understand two walls either of which was a candidate for the sought-for but elusive perimeter wall. Excavation proved the situation was more complicated. One wall bottomed out in the Iron IA, though it did appear to function as a perimeter wall; it may be in this location the perimeter wall migrated due to the changing topography from debris and fill. The other wall was founded at a higher elevation and had a nice cobble surface sealing against it. The floor of the room represented by that surface had a number of broken pottery vessels of different types scattered around. A store jar, though broken, was still held upright in place by the debris which had fallen around it. Though mostly incomplete, the vessels provide an assemblage that will allow us to date the stratum more accurately. Provisionally, it appears probable we have a date in the 10th century BC. This would be our first stratified occupational layer from the Iron IIA if confirmed through further study of the remains.

Field J. Work continued on finding and understanding the rampart layers and their extent. Our first surprise was when Jimmy’s square on the terrace shelf reached bedrock. There was no occupation layer, no Middle Bronze, just bedrock under the buildup of tumbled rock and earth. The next square up, soon also reached bedrock. However a surprise awaited the excavators. A large fissure unfilled with debris was discovered traversing the bedrock from east to west. This must have resulted from a powerful earthquake emanating from the Great Rift Valley just to the west after the bedrock had been buried by layers of sediment. Otherwise, the crack would have filled in with debris. But as it was, the fissure was largely clear of intrusive rocks and earth. A tape measure extended down into the fissure indicated a depth of at least three meters.

The square that had already identified rampart layers at the end of 2014 continued to work on a probe down through those layers hoping to establish whether there was Middle Bronze fortification here on the southern slope as had been found on the western slope. During the last week of excavation Betty’s team here reached bedrock, some 4.5 meters below the surface of the ground. We were surprised that there was only the transitional Late Bronze/Early Iron I rampart all the way to the bottom. No Middle Bronze Age. We had been seeing quite a few of Middle Bronze Age pottery sherds mixed in with later materials all along the southern slope so it was with some surprise that no MB fortifications were located here. Perhaps the settlement was smaller then and thus lies further to the north from where we were excavating. The uppermost square in Field J spent a couple of weeks working carefully through disrupted layers on the outside of the wall found in Field L. The final week revealed the juncture between the disruption and the undisturbed transitional Late Bronze/Early Iron I rampart below, but the wall as also shown in L dated to the Iron I period and not earlier.

Field P, supervised by Freidbert Ninow, proceeded with the challenge of “ground-truthing” the GPR (ground penetrating radar) data in search of possible tombs. In Christine and Larry’s square, excavation in the area of high interest produced a gap between bedrock outcrop and a large boulder. Evidently the GPR had detected the space between the rocks but had not provided clarity on the nature of the opening. The other square led by Kristina with help from Bernina, searching along the escarpment for a tomb entrance, cleared down to bedrock and found only natural contours. Again, the GPR had detected a fracture in the bedrock, and the low-density signal response was taken as indication of a tomb. We now know to be cautious of these kinds in anomalies since natural features can produce them. Not to be discouraged, the P team moved to another location of interest. Following the contour of the shelf on which the dolmen and the dolmen foundation were situated, they excavated an area in search of traces of a third dolmen. But it was not to be. They reached bedrock, bare and simple. While the tombs remain elusive, the efforts of the Field P team have helped us understand the complexity of GPR data interpretation.

Site 84. The first half of the season was taken up by a longer-than-anticipated endeavor by David and Amanda to clear the reservoir. But following our mid-season trip to Petra, we made more rapid progress. The fine example of a wine press which we wished to document was covered with piles of dirt and boulders from recent land-clearing for agricultural activity. The Hopkins were successful in liaising with the landowner to bring in a tractor to remove the bulk of the obscuring debris. Then in a day they had the feature nicely cleared and ready for photogrammetry. We now have a 3D model of one of the finest examples of a wine press in the region. Other accomplishments at Site 84 were the documentation of ancient quarrying, water catchment and containment, and food processing and storage facilities. However, the final two days were spent in excavating a sondage, or sounding, of a newly identified rectilinear structure. Sections of walls and a fine threshold of the building were revealed and enough associated pottery recovered to establish the date of this building in the Late Roman period.

And so we close the season appreciative of the answers achieved, but cognizant of the tremendous potential remaining at this site to illuminate the world of the Bible and Antiquity. From the careful work of students, volunteers, veterans, and other supporters, we bring the past to light again and the legacy of the nameless inhabitants of ancient ‘Umayri lives on.

And so we close the season appreciative of the answers achieved, but cognizant of the tremendous potential remaining at this site to illuminate the world of the Bible and Antiquity. From the careful work of students, volunteers, veterans, and other supporters, we bring the past to light again and the legacy of the nameless inhabitants of ancient ‘Umayri lives on.